Glossolalia

Conjuring the appearance of communication without its content.

Marginalia— notes, doodles, or other payloads placed in the margins of books or even between lines — are fascinating and it’s too bad that we stopped using them. Endnotes and footnotes require a reader to either flip to the entire end of a text or break their concentration and get down to the bottom of the page with their eyes.

Hyperlinks are a poor substitute, and even more likely to distract or derail since you have to follow the link, open a new window or tab, and then return to the original text.

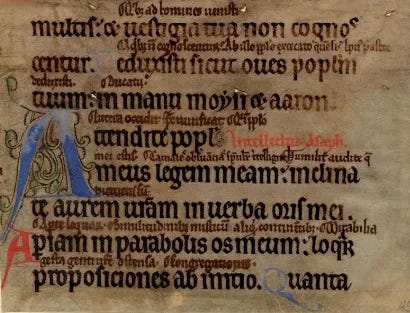

A gloss is a special type of marginalia, designed to define a word or add meaning to a phrase that might be unfamiliar. Glosses were written either between the lines of the main text or in the margin at the same level as the unfamiliar term, or with one leading into the other.

A gloss example, in a medieval manuscript, courtesy of the digital library at the University of Missouri [1]

The ability to keep your place in the text while getting a semantic rundown of an unfamiliar term serves a recognizable purpose, even today 800+ years after this text was produced.

Eventually, marginalia in general fell out of common use, but glosses became collected together into the glossary, where they remain today — if people actually seek them out to have unfamiliar terms explained to them. The authors of texts describing religious law in the medieval period made particular use of glosses and glossaries.

A gloss (Gk. glossa, Lat. glossa, tongue, speech) is an interpretation or explanation of isolated words… A glossary is therefore a collection of words about which observations and notes have been gathered….The canonists of Bologna in particular, favoured the method of the glossarists, and affixed to text and words the meaning which they should bear. [2]

From the glossary eventually came the idea of a general glossary — a list of the meanings of all possible terms — which eventually became the dictionary.

The problem the glossary attends to is a fundamental part of working with data: the lack of a shared semantic understanding between the users of and the generators of data.

A given token, code, string, value, word, or whatever you want to call it can have various meanings to different audiences and in different contexts. LLMs calculate and embed this contextual relationship across vast corpora of text via their embeddings, but most electronic systems exchange these tokens or codes in isolation.

In short, this means that some system outputs a O or a 2 and the end user often need to reason about, intuit, and decide what that code was supposed to mean. ****In healthcare, specific external systems of taxonomy and terminology help fill some of this gap, such as ICD-10-CM or NUCC Place of Service codes. Regardless, not everything is covered by a standard, and the specific implementations of standards differ over time and between actors.

Language itself is prone to this kind of glossal failure — how many times have you encountered misunderstandings between yourself and even those closest to you over the meaning of specific words or phrases — especially in async electronic communication via text?

Usage of terms without definitions leads to another phenomenon (at least metaphorically) — glossolalia — the production of sounds and words that appear to be a language but that are not. I mean this in the linguistic sense, not in the sense of the religious or cultural practice of ‘speaking in tongues.’

glossolalia, (from Greek glōssa, “tongue,” and lalia, “talking”), utterances approximating words and speech, usually produced during states of intense religious experience. The vocal organs of the speaker are affected; the tongue moves, in many cases without the conscious control of the speaker; and generally unintelligible speech pours forth [3].

Linguistically, glossolalia is the production of sounds that appear to have the structure of a known language, but that do not constitute a known language and their meaning is not understood by the speaker or the audience. I adapt that linguistic term to describe the phenomenon of people trying to communicate but instead only conjuring the appearance of communication.

I think most of us have had the experience of having a conversation or reading a piece of writing in a work context and coming away thoroughly confused by what was intended to be communicated. Gulfs in context between speakers or communicators — commercial vs technical, client-focused vs product-focused, different thought disciplines — contribute to this problem, which can cause serious misallocations of effort and significant grief and upheaval in organizations.

I think that slowing down and finding the agreed upon definitions of key terms — adding glosses — to our communication could help avoid this kind of miscommunication. Wider usage of standard taxonomies and ontologies would help. Someday, this may all be incorporated into the operation of every data system — the vaunted‘semantic layer’— but, until then, we’ll have to continue being comfortable with glossolalia at least some of the time.

[1] https://library.missouri.edu/specialcollections/exhibits/show/glossary/page4

[2] Boudinhon, Auguste. "Glosses, Glossaries, Glossarists." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 6. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1909. http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/06588a.htm.